The Ennui of Late Socialism in Binka Zhelyazkova’s The Swimming Pool

“With the development of socialism, the desire to build a bright future is replaced by the desire to live in an already built and refined, well-ordered socialist life. Overalls have been replaced by short skirts, picks and shovels by televisions. Instead of pushing the rock up the hill at an accelerated pace, Sisyphus enjoys its aimless rolling. This is the phase of middle-class socialism.”

–Cristofer Scarboro, Sisyphus Revisited: Consumption and Collapse in Late Socialist Bulgaria

After her prom night, as her classmates celebrate their graduation by a swimming pool, Bela (Yanina Kasheva) contemplates suicide by jumping off the pool’s tower. There, she meets Apostol (Kosta Tsonev), a middle-aged architect and ex-partisan who later introduces her to his best friend Bufo (Kliment Denchev). An unlikely triangle forms: between friendship, jealousy, and budding romance.

Exemplary of her late work, The Swimming Pool is one of Binka Zhelyazkova’s very few films shot in colour, and the first of a trilogy, along with The Big Night Swim (1980), part of Cannes’ Un Certain Regard that year, and her last film On The Roofs at Night (1988).

While her previous films were dedicated to partisans, female prisoners, and villagers, The Swimming Pool explores a new social stratum – communism’s middle class and its bohemians. For the privileged and the conformists, the 1970s in Bulgaria were a time of relative freedom and comfort – as the government tried to reinforce a sense of a free society, some doors to the West (those to certain music, art, or fashion trends) were now slightly ajar.

In this socialist modernity, like in modernity on the other end of the Iron Curtain, Bela experiences a state of meaninglessness and dissatisfaction. In it, quotidian reality equals boredom, while partisans have been reduced to symbols of a glorified past that the new generation is largely indifferent to.

Unlike Zhelyazkova’s previous work, The Swimming Pool examines and challenges the topics that torture the middle class – belonging, the search for meaning, sexuality, love triangles, and coming of age. In the comfort of Central Sofia, the struggle for a better life for all (such as the building of a new hospital, for example), has transcended from a revolutionary act to a philosophical question, or a rejected architectural proposal at best.

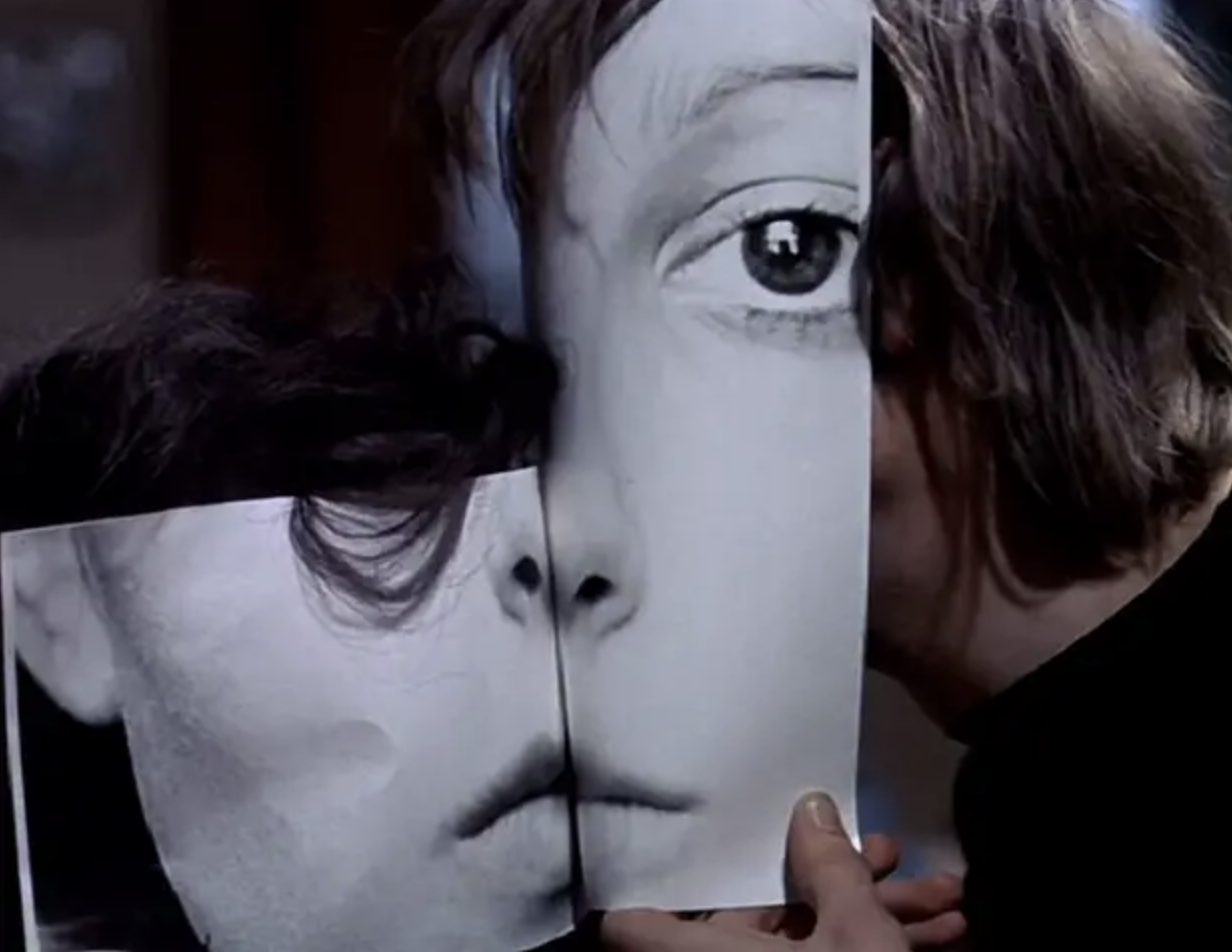

Binka Zhelyazkova and DoP Ivaylo Trenchev during the filming of The Swimming Pool. Image courtesy of Svetla Ganeva.

It is this disenchantment with the communist reality that manifests itself throughout most of Zhelyazkova’s films. But besides the exploration of those new socialist realities, The Swimming Pool marks another important shift in the filmmaker’s career. Using architecture as both a character and a set, the film intersects fiction with daily reality, including improvised scenes with passers-by, such as the scene where Bufo interviews Sofians about the meaning of silence

This fascination with the real world will stay with Zhelyazkova, and she will later make two documentaries about the lives of female prisoners – a topic she first explored in her fiction film The Last Word (1973).

The text was originally published as programme notes for the Barbican Centre.